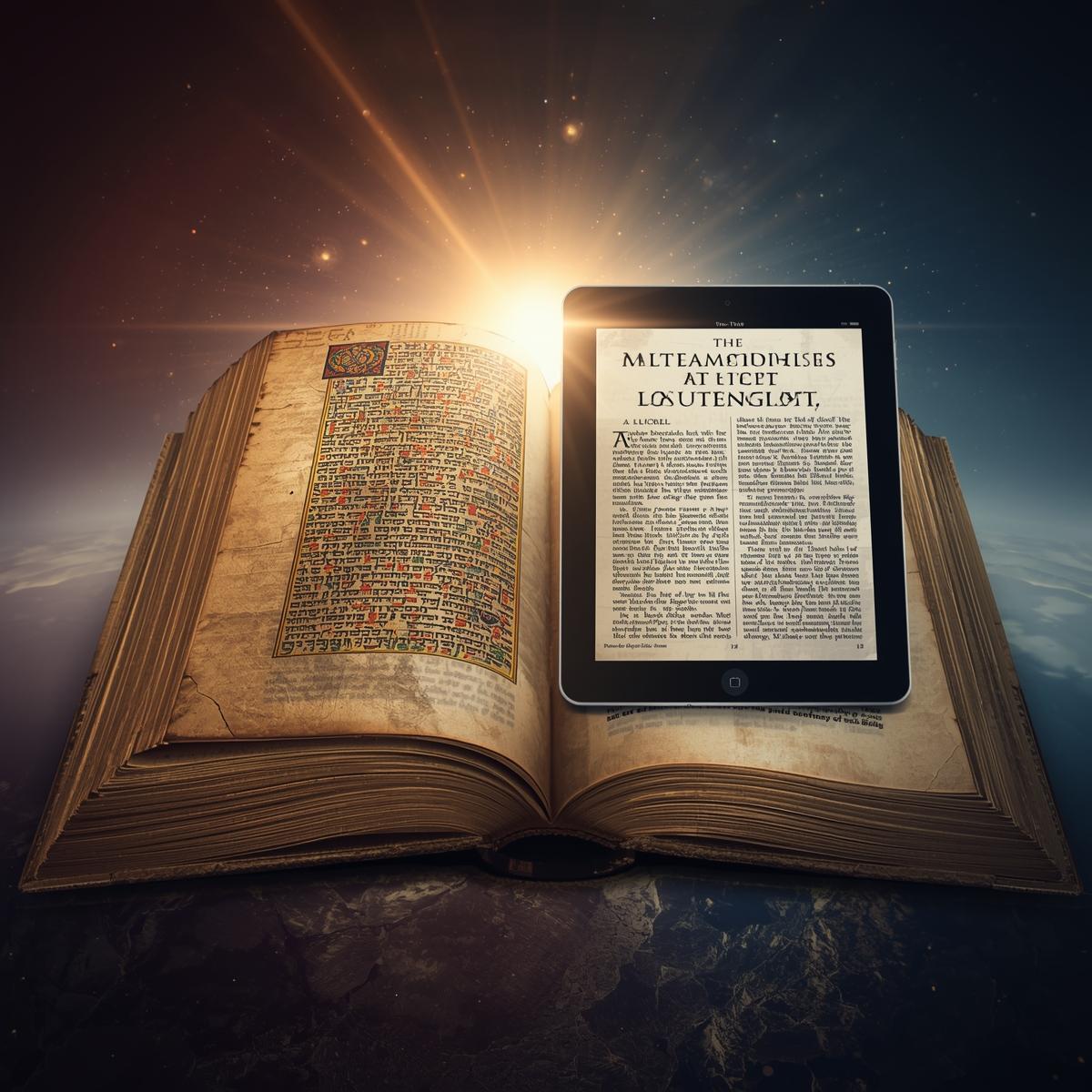

Dud you know before the printing press,every Bible was a handmade masterpiece?

That’s why the Bible remains the Unchanging Message in changing forms.

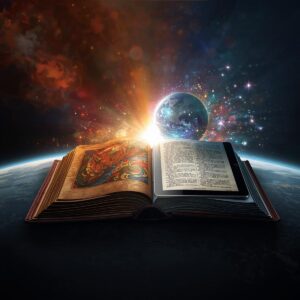

The Bible is also the best-selling book of all time, a spiritual cornerstone for billions of people, and a foundational text of Western civilization. Yet, the Bible as we know it today is not a single, static book that fell from heaven in its current form. It is the product of an incredible metamorphosis, a journey spanning millennia, languages, cultures, and technological revolutions. From painstakingly handwritten scrolls to the instant digital texts on our phones, the story of the Bible is as dynamic as its message.Let’s trace this wonderful journey.

The Dawn of Divine Words: Oral Tradition & The First Scrolls

Long before “books” existed, the stories of the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament) were passed down orally. Eventually, they were inscribed on scrolls made of papyrus or parchment (animal skin). These were expensive, fragile, and required immense skill to produce.

- The Septuagint (c. 3rd-2nd Century BC): A pivotal moment in history. This is the first major translation, where Hebrew scriptures were translated into Koine Greek in Alexandria, Egypt. Legend says 70 (or 72) scholars worked independently and produced identical translations! The Septuagint became the scripture of the early Church and was widely quoted by the New Testament writers.

The Vulgate: Jerome’s Latin Masterpiece

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, a reliable, uniform Latin text was needed to replace older, inconsistent translations.

- Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (c. 382-405 AD): Commissioned by Pope Damasus I, the scholar Jerome undertook the mammoth task of translating the Bible from its original Hebrew and Greek into common Latin (the Vulgate). His work, which took decades, became the definitive Bible of Western Christianity for over a thousand years. It standardized scripture and shaped theological language for centuries.

The White Cliffs of Preservation: Monastic Scribes

During the early Middle Ages, as the Roman Empire crumbled, the task of preserving knowledge, including the Bible, fell to monastic communities. In scriptoriums, often cold and dimly lit rooms, monks would spend years, sometimes their entire lives, meticulously copying the text of the Latin Vulgate.

- The Work of the Scribes: This was not mere copying; it was an act of devotion. They developed beautiful, uniform scripts to improve legibility. They illuminated the pages with stunning artwork, gold leaf, and intricate designs, transforming the Bible into a sacred object of immense beauty and value. These manuscripts were often “chained” to libraries to prevent theft. For centuries, these anonymous scribes were the sole guardians of the Word, ensuring its physical survival through the “Dark Ages.”

The Wycliffe Manuscripts: The First English Bible

Centuries before Gutenberg, a seismic shift began not with technology, but with an idea: that the common person should be able to read the Bible in their own language.

- John Wycliffe (c. 1320s-1384): An Oxford theologian and reformer, Wycliffe argued that the Bible, not the Pope, was the ultimate Christian authority. He believed everyone should have access to it, not just priests who could read Latin.

- The Handwritten Heresy: In the 1380s, Wycliffe and his followers (dubbed “Lollards”) undertook the monumental task of translating the entire Bible from the Latin Vulgate into Middle English. This was a dangerous act, as the Church hierarchy saw it as a threat to their authority.

- The Metamorphosis of Dissemination: Since the printing press was still 70 years in the future, every single copy of the Wycliffe Bible had to be painstakingly handwritten by scribes. It was an enormous, clandestine effort. While not as artistically illuminated as the monastic Bibles, these manuscripts were revolutionary. They were copied and circulated widely, often at great personal risk. Owning or reading a Wycliffe Bible was considered heresy, and his followers were persecuted, yet the movement persisted.

The Wycliffe Bible represents a critical metamorphosis: the shift from the Bible as a controlled, Latin object of the clergy to a living, accessible text for the English-speaking laity.

The Gutenberg Revolution: The Bible for the People

The next great leap came with technology, which solved the problem of scale that the Wycliffe movement faced.

- The Gutenberg Bible (c. 1455): Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the mechanical movable-type printing press shattered the manuscript era. The Gutenberg Bible (also a Latin Vulgate) was his first major book. For the first time, multiple identical copies of the Bible could be produced relatively quickly and cheaply. This didn’t just make Bibles more accessible; it fueled the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the democratization of knowledge itself. The handwritten era was, for all practical purposes, over.

A Quick Recap

- The First Translation of the Bible Was into Greek: The Septuagint (3rd-2nd century BC) is the first major translation of the Hebrew Bible. Its name comes from the legend that 70 (or 72) scholars in Alexandria independently translated the entire text and produced 70 identical Greek versions.

- Jerome’s “Vulgate” Was a Bestseller for 1,000+ Years: The Latin Vulgate, translated by Jerome in the late 4th century, became the standard Bible for Western Christianity for over a millennium. It was called “Vulgate” because it was written in the vulgus, or the common (Latin) speech of the people.

- The First English Bible Was a Handwritten Heresy: The Wycliffe Bible (1380s) was the first complete Bible in English. Since the printing press didn’t exist yet, every single copy had to be painstakingly handwritten by scribes. The Church considered it illegal, and people caught with a copy could be executed.

- Gutenberg’s Bible Bankrupted Its Inventor: The Gutenberg Bible (1455) was the first major book printed in Europe with movable type. While it revolutionized the world, Johannes Gutenberg himself saw little profit from it; his financial backer sued him and took over his business, leaving Gutenberg in debt.

- The Geneva Bible was the “Pilgrim’s Bible”: Before the King James Version, the Geneva Bible (1560) was the most popular English Bible. It was the Bible of Shakespeare, the Puritans, and the Pilgrims on the Mayflower. It was also the first English Bible to use verse numbers and was filled with revolutionary, anti-tyranny study notes.

- The King James Version was a “Committee Project”: The King James Version (1611) was created by six committees of scholars, totalling about 50 men. Despite its later status, it was not an immediate popular success, as many people were loyal to the Geneva Bible for decades.

- We Have Thousands of Ancient Manuscripts: No original manuscripts of the biblical books exist. However, the New Testament is supported by an unparalleled wealth of ancient copies over 5,800 Greek manuscriptsfar more than any other ancient text, allowing scholars to reconstruct the original with incredible accuracy.